This

story for us began four or five years ago. Linda Gorski and I were

walking along the banks of Buffalo Bayou in the downtown area trying to

identify the sites that might hold good stories for our upcoming book

on Houston along Buffalo Bayou. We came upon the large oak tree in

front of what was then the Albert Thomas Convention Center, and we

noted that the sign by the tree said it was the Old Hanging Oak. We

made a note to find out more about the story of the tree. Then, a

couple of years ago, we ran into Stephen Hardin at a local event and he

told us that he had just published a book on the 1838 executions of two

convicted murderers in a location that was later called Hangman’s

Grove. That’s when we began to link the stories together. With a

little help from Jim Glass, things began to fall into place. What

follows is what we found out…

In 1836, Houston emerged as a

town from the wilderness on the frontier of Texas. Today, you would

scarcely see anything that resembles a wilderness in Houston, but the

traces of the past are still there and they are intertwined into our

local history.

In 1836, Houston emerged as a

town from the wilderness on the frontier of Texas. Today, you would

scarcely see anything that resembles a wilderness in Houston, but the

traces of the past are still there and they are intertwined into our

local history.

Buffalo Bayou, unlike most rivers in Texas, runs east-west instead of north-south. It is the dividing line between the East Texas Piney Woods to the north and the Coastal Prairie to the south. The banks along the bayou were covered with a riparian woodland and the nearby prairie was dotted with small thickets of oak and other native trees. Our story involves three of these tree clusters.

As you might know, large trees, especially very large oak trees, are held in high esteem in many parts of the country. Some trees even have their own societies that rank their magnificent trees by size, age, girth, etc. A few years back, we came upon Houston’s own “special” live oak tree while exploring the banks of Buffalo Bayou. Houston’s largest live oak tree sits in front of The Planet, an internet hosting company located in the newly renovated section of Bayou Place, formerly the Albert Thomas Convention Center.

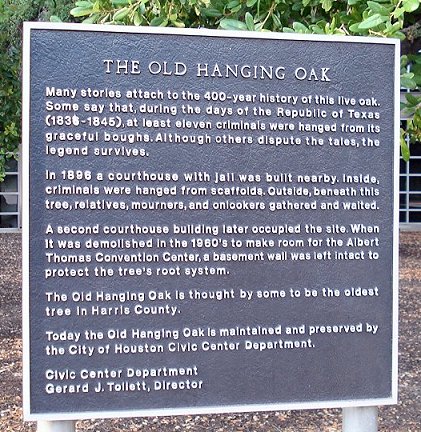

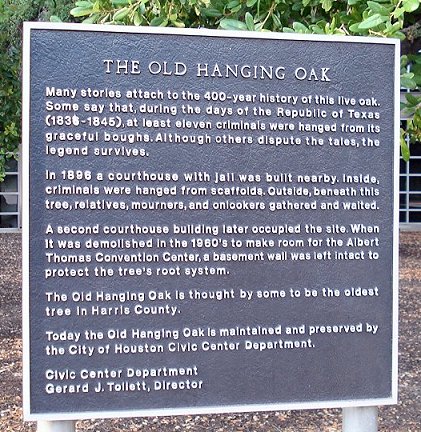

This tree, which is located on the corner of Capitol Avenue and Bagby Street, appears to my untrained eye (and please correct me if I am wrong) to be a Texas Live Oak, Quercus fusiformis. A marker that has been placed in front of this tree by the City of Houston estimates the age of this live oak to be about 400 years.

As a side note, we did try to verify the age of

the tree that the marker says might be 400 years old. Determining the

age of a tree is not as easy as it may seem. Several sources say that

the only accurate way to determine the age of a tree is to count the

growth rings. To do that, you have to cut it down (!) or use a boring

tool. Since we had access to neither of those options, we tried the

other technique which is to measure the circumference of the trunk of

the tree.

As a side note, we did try to verify the age of

the tree that the marker says might be 400 years old. Determining the

age of a tree is not as easy as it may seem. Several sources say that

the only accurate way to determine the age of a tree is to count the

growth rings. To do that, you have to cut it down (!) or use a boring

tool. Since we had access to neither of those options, we tried the

other technique which is to measure the circumference of the trunk of

the tree.

One morning in August, we drove over to the tree with a measuring tape and a pencil. Two mounted patrol officers gave us a long, hard look, but they refrained from asking us what we were doing. We strung the tape measure around the tree trunk, twice in fact, to find that the tree is 175 inches around. Then, we plugged that number into the step by step calculations offered by four different web sites for a sure fire answer. We got four widely different results, ranging from 136 years to over 300 years. None actually approached the 400 year number, though. So, the true age of our oak tree will have to wait for a more scientific analysis. What we do know, is: that tree is old.

The marker also has given the tree the name of The Old Hanging Oak. It is a name which we feel is unfortunate for this tree, and it is a name that is historically inaccurate in many ways. In particular, the marker repeats the undocumented legend that, during the period of the Republic of Texas, eleven criminals were executed by hanging from this tree.

It is almost a part of the myth of the American West that every town on the frontier had a "hanging tree" on the square or somewhere in the locality. In Texas, several towns boast of “hanging trees,” including Clarksville on whose tree, in 1837, a murderer named Page and two others were hung, and Goliad, where, in 1857, trials were held and men were hanged from the local oak for the murder of Mexican freighters. Comanche, Seguin, Cold Spring and Hallettsville also boast of their hanging trees, just to name a few.

In a perverse sense of pride, these legendary trees are pointed to in the local histories. Whether these trees actually performed the roles assigned to them is a matter for local historians to document or debunk. Legends, however, are difficult to deflate, and their advocates do not give up the tantalizing story easily, no matter how outlandish it may be.

Generally, the naming of a hanging tree refers to a single event in the distant past. So significant was this event that it remains in the memory of the town and the local population long after the event. It may have a basis in fact, but the legend takes on a life of its own. So, then, does Houston have an event in its past that would give rise to the legend of the hanging tree? In fact, it does.

On Wednesday, March 28, 1838, convicted

murderers John Christopher Columbus Quick and David James Jones were

executed. The gallows were located, according to the local newspaper

that day, "in a beautiful islet of timber, situated in the prairie

about a mile south of the city.” As described by the first hand

account of John Herndon, a young lawyer who arrived in Houston from

Kentucky in January, 1838, the hangings were a gruesome affair that out

of curiosity drew almost everyone in the young city to the place that

would later be called “Hangman’s Grove”.

On Wednesday, March 28, 1838, convicted

murderers John Christopher Columbus Quick and David James Jones were

executed. The gallows were located, according to the local newspaper

that day, "in a beautiful islet of timber, situated in the prairie

about a mile south of the city.” As described by the first hand

account of John Herndon, a young lawyer who arrived in Houston from

Kentucky in January, 1838, the hangings were a gruesome affair that out

of curiosity drew almost everyone in the young city to the place that

would later be called “Hangman’s Grove”.

For the young town, the executions made a big impression. Nearly every person in town witnessed the event and it was remembered by the citizens of Houston for decades. The place of execution soon became known as Hangman’s Grove. But, since the early 20th century, the exact location of Hangman’s Grove has been a matter of debate among modern historians. The debate continues even today.

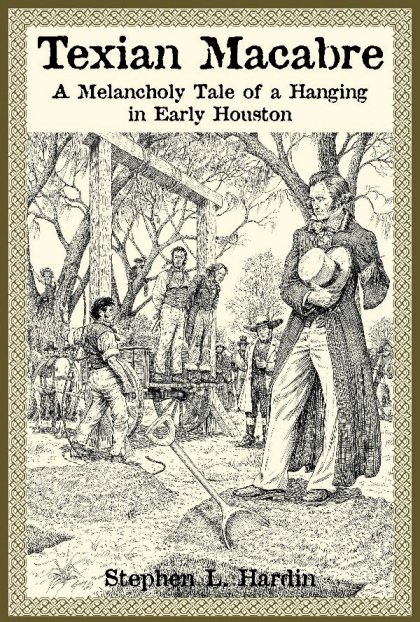

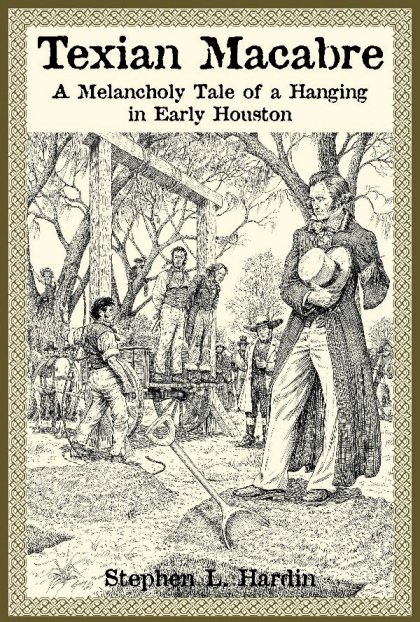

Historian Stephen L. Hardin wrote the story of the 1838 Quick and Jones hangings in his popular book entitled Texian Macabre. In exquisite detail, Hardin tells the story of how the prosecution of these criminals changed the sense of lawlessness that had captivated the capital of the Republic in its first years of existence. The executions set a new tone of civility for Houston.

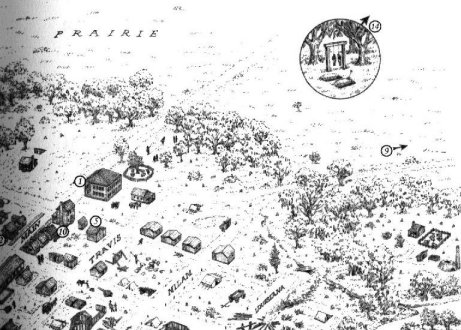

As a historian, Hardin relied on

the notes of Andrew Muir, a historian of Houston from a generation

earlier, when he identified the location of the execution site as

“in the vicinity of Main and Webster.” Both men were quite

vague in saying where the place was. This can be seen in the map included in Hardin’s book.

As a historian, Hardin relied on

the notes of Andrew Muir, a historian of Houston from a generation

earlier, when he identified the location of the execution site as

“in the vicinity of Main and Webster.” Both men were quite

vague in saying where the place was. This can be seen in the map included in Hardin’s book.

By 1839, a year after the events described above, the name Hangman’s Grove appears in an advetisement in the Telegraph and Texas Register as well as in the deed records of Harris County. The February 13, 1839 edition of the Telegraph contains an advertisement by the company of Heddenberg and Vedder which mentions their tract of land which includes part of "hangman's grove." In fact, the ad is a warning notice to the public forbidding the cutting and removal of timber from the tract. About a month later, on March 26, 1839, the John W. N. A. Smith Survey report describes Hangman's Grove as extending along the James Wells Survey west boundary line for .65 miles.

Hangman's Grove was mentioned in another newspaper ad on June 19, 1839 by the Hedenberg & Vedder mercantile firm for 15 acres within 1 mile of the city. Similarly, on March 2, 1841, Mary O'Brien sold 15-1/2 acres near Hangman's Grove to Emma Blake. The land was located in the Girard tract about a half mile from Houston. The Girard tract was in the James Wells Survey. On January 1, 1840, James Wells and his wife sold 31-1/2 acres from his headright to Auguste Girard, Charles J. Hedenberg and Philip V. Vedder, a triangular piece of land in the extreme southern part of the Wells survey. Following the details of the Smith Survey report, Andrew Muir identified this Hangman's Grove, about 1950, as near City of Houston Block 245, bounded by Lamar Avenue, Dallas Avenue, Chartres Street and St. Emanuel Street.

The question is: which place is the real Hangman’s Grove? Main at Webster or Block 245? We can assess each possible site by asking if the place is the site of a documented event. And, did the site remain in the popular memory because of that event?

For Block 245, we have found no documentation or reports of a significant event of a hanging or an execution in the grove near this block. In addition, according to the survey report, the grove extends for over a half mile. Much larger than the “islet” description for the location of the Quick and Jones executions. The survey report also notes that the grove of timber begins a half mile from the city. Subsequent deed records and other accounts make no mention of this “Hangman’s Grove” after 1841.

The evidence for Muir’s Main at Webster location as the actual site of the Quick and Jones executions is somewhat better. This location is referred to as Hangman’s Grove in a number of newspaper stories throughout the 19th century. The Galveston Daily News of January 28, 1874 reported on cases of small pox, one of whom was a black man who had been sick for sometime and lived “at Hangman's Grove, in the west of the city.” On August 12, 1876, the Galveston Daily News reported that a dueling incident between two African-Americans took place “in the pine woods known as Hangman's Grove, near State Fair Park.” The fairgrounds were located near Webster Street and west of Main Street. Frank Barnes, who lived "in the vicinity of Hangman's Grove, in the western part of the city" was the victim of a robbery, according to Galveston Daily News of June 17, 1877. Each of these newspaper accounts points to the general knowledge that the Hangman’s Grove was a thicket of trees in the area that is southwest of downtown Houston.

An article in the Galveston Daily News of August 5, 1893, offers even more information regarding Hangman’s Grove. The story reported that there were two other hangings that took place at the City’s Hangman’s Grove, one, in 1854, was a Mr. Hyde and the other, in 1867, was a Mr. Johnson. After that, hangings took place in the jail yard of the county jail in downtown. These included the executions of Henry Quarles in 1878, John Cone in 1881, Burt Mitchell in 1885, William Caldwell in 1889 and Henry McGee in 1891.

Well into the late 19th century, the cluster of trees that was called Hangman’s Grove was a well- known locale to the people of Houston. Most likely, this was because the grove was still there and had changed little since 1838. It was a landmark on the prairie southwest of town. The clincher in terms of the exact location of Hangman’s Grove, however, comes in 1887. The Galveston Daily News of August 23, 1887, reported that Peter Gabel owned the twenty acre grove of trees in south part of the 4th Ward that was known as old Hangman's Grove. Gabel fenced off the tract and thus blocked several unsurveyed streets including Calhoun Street, Gray Street and Pierce Street, Baker Street, Hopson Street and Crosby Street, Anson Street, Bagby Street and Brazos Street.

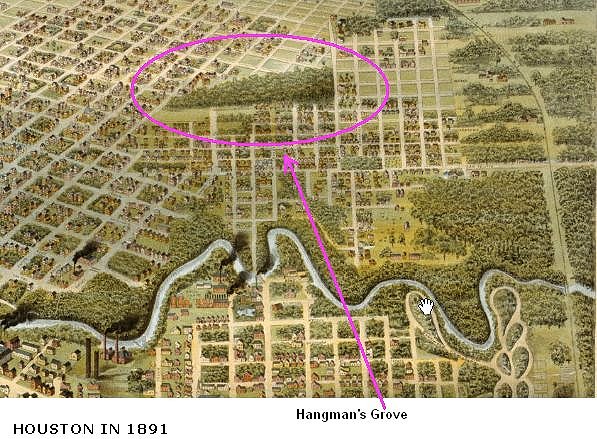

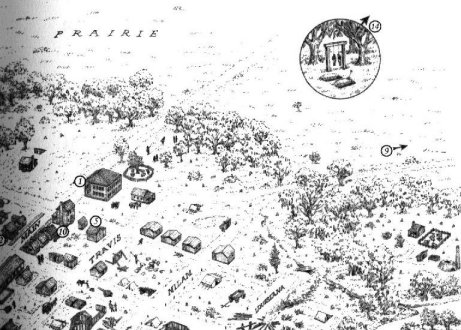

The Gabel tract which

contained Hangman’s Grove had been purchased by Gabel’s

wife’s first husband John Stein from Obedience Smith in 1843. The

deed records clearly define the bounds of the land where the grove was,

as late as 1887. Lastly, the Bird’s Eye map of Houston, printed

in 1891, clearly shows Hangman’s Grove. It provides a final bit

of evidence that the grove of trees that acquired the name of

Hangman’s Grove after the executions of 1838 was still a

prominent feature of town

over 50 years later. The subsequent suburban development of the land

had the effect of removing the grove as a local landmark. As a result,

few, if any, references can be found to Hangman’s Grove after

1900. By the time of the serious study of Houston’s history in

the 1940’s, the location of the grove had been forgotten.

The Gabel tract which

contained Hangman’s Grove had been purchased by Gabel’s

wife’s first husband John Stein from Obedience Smith in 1843. The

deed records clearly define the bounds of the land where the grove was,

as late as 1887. Lastly, the Bird’s Eye map of Houston, printed

in 1891, clearly shows Hangman’s Grove. It provides a final bit

of evidence that the grove of trees that acquired the name of

Hangman’s Grove after the executions of 1838 was still a

prominent feature of town

over 50 years later. The subsequent suburban development of the land

had the effect of removing the grove as a local landmark. As a result,

few, if any, references can be found to Hangman’s Grove after

1900. By the time of the serious study of Houston’s history in

the 1940’s, the location of the grove had been forgotten.

So, then, what about the Old Hanging Oak?

John H. S. Stanley built his homestead in the isolated tract on the west side of town in the 1840’s. Stanley was the local representative of Thomas Affleck, a nurseryman in Brenham. He planted a grove of ornamental trees around Stanley home. The Stanley family lived on the property until the 1880’s when it was sold and later acquired by the County in 1895 for a courthouse and jail. The four story courthouse and jail was built on the Stanley land and the large live oak tree which graced the property was left in place to stand at the front entrance to the building. When this courthouse was demolished in 1926 for the construction of a new, eight story courthouse and jail complex, the live oak again survived and became a landmark in its own right at the front of the courthouse.

When asked if any hangings had taken place from the oak, T. A. Binford, who served as the sheriff of Harris County from 1918 to 1937, said that the criminals were hanged from the rafters of the jail, but beneath the tree, the relatives and mourners gathered and waited. In 1942, the live oak at the courthouse was simply referred to as “an immense spreading oak…” By 1984, noted reporter and newsman Ray Miller called it “the Courthouse Oak, also known as the Hanging Oak…” When the City was upgrading the Civic Center complex in the early 1990’s, the marker placed at the tree called it “The Old Hanging Oak”.

No hangings or executions took place at this fine live oak tree. It was called the Courthouse Oak in the past. Wouldn’t this be a better name for our beloved old tree today?

All material printed on

this

page

and this web site is copyrighted. All rights reserved. In 1836, Houston emerged as a

town from the wilderness on the frontier of Texas. Today, you would

scarcely see anything that resembles a wilderness in Houston, but the

traces of the past are still there and they are intertwined into our

local history.

In 1836, Houston emerged as a

town from the wilderness on the frontier of Texas. Today, you would

scarcely see anything that resembles a wilderness in Houston, but the

traces of the past are still there and they are intertwined into our

local history.Buffalo Bayou, unlike most rivers in Texas, runs east-west instead of north-south. It is the dividing line between the East Texas Piney Woods to the north and the Coastal Prairie to the south. The banks along the bayou were covered with a riparian woodland and the nearby prairie was dotted with small thickets of oak and other native trees. Our story involves three of these tree clusters.

As you might know, large trees, especially very large oak trees, are held in high esteem in many parts of the country. Some trees even have their own societies that rank their magnificent trees by size, age, girth, etc. A few years back, we came upon Houston’s own “special” live oak tree while exploring the banks of Buffalo Bayou. Houston’s largest live oak tree sits in front of The Planet, an internet hosting company located in the newly renovated section of Bayou Place, formerly the Albert Thomas Convention Center.

This tree, which is located on the corner of Capitol Avenue and Bagby Street, appears to my untrained eye (and please correct me if I am wrong) to be a Texas Live Oak, Quercus fusiformis. A marker that has been placed in front of this tree by the City of Houston estimates the age of this live oak to be about 400 years.

As a side note, we did try to verify the age of

the tree that the marker says might be 400 years old. Determining the

age of a tree is not as easy as it may seem. Several sources say that

the only accurate way to determine the age of a tree is to count the

growth rings. To do that, you have to cut it down (!) or use a boring

tool. Since we had access to neither of those options, we tried the

other technique which is to measure the circumference of the trunk of

the tree.

As a side note, we did try to verify the age of

the tree that the marker says might be 400 years old. Determining the

age of a tree is not as easy as it may seem. Several sources say that

the only accurate way to determine the age of a tree is to count the

growth rings. To do that, you have to cut it down (!) or use a boring

tool. Since we had access to neither of those options, we tried the

other technique which is to measure the circumference of the trunk of

the tree. One morning in August, we drove over to the tree with a measuring tape and a pencil. Two mounted patrol officers gave us a long, hard look, but they refrained from asking us what we were doing. We strung the tape measure around the tree trunk, twice in fact, to find that the tree is 175 inches around. Then, we plugged that number into the step by step calculations offered by four different web sites for a sure fire answer. We got four widely different results, ranging from 136 years to over 300 years. None actually approached the 400 year number, though. So, the true age of our oak tree will have to wait for a more scientific analysis. What we do know, is: that tree is old.

The marker also has given the tree the name of The Old Hanging Oak. It is a name which we feel is unfortunate for this tree, and it is a name that is historically inaccurate in many ways. In particular, the marker repeats the undocumented legend that, during the period of the Republic of Texas, eleven criminals were executed by hanging from this tree.

It is almost a part of the myth of the American West that every town on the frontier had a "hanging tree" on the square or somewhere in the locality. In Texas, several towns boast of “hanging trees,” including Clarksville on whose tree, in 1837, a murderer named Page and two others were hung, and Goliad, where, in 1857, trials were held and men were hanged from the local oak for the murder of Mexican freighters. Comanche, Seguin, Cold Spring and Hallettsville also boast of their hanging trees, just to name a few.

In a perverse sense of pride, these legendary trees are pointed to in the local histories. Whether these trees actually performed the roles assigned to them is a matter for local historians to document or debunk. Legends, however, are difficult to deflate, and their advocates do not give up the tantalizing story easily, no matter how outlandish it may be.

Generally, the naming of a hanging tree refers to a single event in the distant past. So significant was this event that it remains in the memory of the town and the local population long after the event. It may have a basis in fact, but the legend takes on a life of its own. So, then, does Houston have an event in its past that would give rise to the legend of the hanging tree? In fact, it does.

On Wednesday, March 28, 1838, convicted

murderers John Christopher Columbus Quick and David James Jones were

executed. The gallows were located, according to the local newspaper

that day, "in a beautiful islet of timber, situated in the prairie

about a mile south of the city.” As described by the first hand

account of John Herndon, a young lawyer who arrived in Houston from

Kentucky in January, 1838, the hangings were a gruesome affair that out

of curiosity drew almost everyone in the young city to the place that

would later be called “Hangman’s Grove”.

On Wednesday, March 28, 1838, convicted

murderers John Christopher Columbus Quick and David James Jones were

executed. The gallows were located, according to the local newspaper

that day, "in a beautiful islet of timber, situated in the prairie

about a mile south of the city.” As described by the first hand

account of John Herndon, a young lawyer who arrived in Houston from

Kentucky in January, 1838, the hangings were a gruesome affair that out

of curiosity drew almost everyone in the young city to the place that

would later be called “Hangman’s Grove”.“Wednesday,

March 28 – A delightful day, worthy of other deeds. One hundred

Forty men ordered out to guard the criminals to the gallows. A

concourse of from 2,000 to 3,000 persons on the ground and among the

whole lot not a single sympathetic tear was dropped. Quick addressed

the crowd in a stern, composed and hardened manner, entirely unmoved up

to the moment of swinging off the cart. Jones seemed frightened

although as hardened in crime as Quick. They swung off at 2

o’clock p.m. and were cut down in thirty five minutes, not having

made the slightest struggle. Cavanaugh and (myself) went out to the

graves and cut off the heads of Quick and Jones and brought them in for

dissection.”

“Thursday, March 29 – Commended dissecting and examining the heads. Phrenologically, Jones had a very bad head, all moral power very deficient. Quick had a much better head. His moral powers pretty well developed and intellectual tolerably well.”

“Friday, March 30 – Finished the dissection of Quick’s and Jones heads. Preserved the brains of Jones.”

“Saturday, March 31 – Buried the remains of Quick’s and Jones heads.”

“Thursday, March 29 – Commended dissecting and examining the heads. Phrenologically, Jones had a very bad head, all moral power very deficient. Quick had a much better head. His moral powers pretty well developed and intellectual tolerably well.”

“Friday, March 30 – Finished the dissection of Quick’s and Jones heads. Preserved the brains of Jones.”

“Saturday, March 31 – Buried the remains of Quick’s and Jones heads.”

For the young town, the executions made a big impression. Nearly every person in town witnessed the event and it was remembered by the citizens of Houston for decades. The place of execution soon became known as Hangman’s Grove. But, since the early 20th century, the exact location of Hangman’s Grove has been a matter of debate among modern historians. The debate continues even today.

Historian Stephen L. Hardin wrote the story of the 1838 Quick and Jones hangings in his popular book entitled Texian Macabre. In exquisite detail, Hardin tells the story of how the prosecution of these criminals changed the sense of lawlessness that had captivated the capital of the Republic in its first years of existence. The executions set a new tone of civility for Houston.

As a historian, Hardin relied on

the notes of Andrew Muir, a historian of Houston from a generation

earlier, when he identified the location of the execution site as

“in the vicinity of Main and Webster.” Both men were quite

vague in saying where the place was. This can be seen in the map included in Hardin’s book.

As a historian, Hardin relied on

the notes of Andrew Muir, a historian of Houston from a generation

earlier, when he identified the location of the execution site as

“in the vicinity of Main and Webster.” Both men were quite

vague in saying where the place was. This can be seen in the map included in Hardin’s book.By 1839, a year after the events described above, the name Hangman’s Grove appears in an advetisement in the Telegraph and Texas Register as well as in the deed records of Harris County. The February 13, 1839 edition of the Telegraph contains an advertisement by the company of Heddenberg and Vedder which mentions their tract of land which includes part of "hangman's grove." In fact, the ad is a warning notice to the public forbidding the cutting and removal of timber from the tract. About a month later, on March 26, 1839, the John W. N. A. Smith Survey report describes Hangman's Grove as extending along the James Wells Survey west boundary line for .65 miles.

Hangman's Grove was mentioned in another newspaper ad on June 19, 1839 by the Hedenberg & Vedder mercantile firm for 15 acres within 1 mile of the city. Similarly, on March 2, 1841, Mary O'Brien sold 15-1/2 acres near Hangman's Grove to Emma Blake. The land was located in the Girard tract about a half mile from Houston. The Girard tract was in the James Wells Survey. On January 1, 1840, James Wells and his wife sold 31-1/2 acres from his headright to Auguste Girard, Charles J. Hedenberg and Philip V. Vedder, a triangular piece of land in the extreme southern part of the Wells survey. Following the details of the Smith Survey report, Andrew Muir identified this Hangman's Grove, about 1950, as near City of Houston Block 245, bounded by Lamar Avenue, Dallas Avenue, Chartres Street and St. Emanuel Street.

The question is: which place is the real Hangman’s Grove? Main at Webster or Block 245? We can assess each possible site by asking if the place is the site of a documented event. And, did the site remain in the popular memory because of that event?

For Block 245, we have found no documentation or reports of a significant event of a hanging or an execution in the grove near this block. In addition, according to the survey report, the grove extends for over a half mile. Much larger than the “islet” description for the location of the Quick and Jones executions. The survey report also notes that the grove of timber begins a half mile from the city. Subsequent deed records and other accounts make no mention of this “Hangman’s Grove” after 1841.

The evidence for Muir’s Main at Webster location as the actual site of the Quick and Jones executions is somewhat better. This location is referred to as Hangman’s Grove in a number of newspaper stories throughout the 19th century. The Galveston Daily News of January 28, 1874 reported on cases of small pox, one of whom was a black man who had been sick for sometime and lived “at Hangman's Grove, in the west of the city.” On August 12, 1876, the Galveston Daily News reported that a dueling incident between two African-Americans took place “in the pine woods known as Hangman's Grove, near State Fair Park.” The fairgrounds were located near Webster Street and west of Main Street. Frank Barnes, who lived "in the vicinity of Hangman's Grove, in the western part of the city" was the victim of a robbery, according to Galveston Daily News of June 17, 1877. Each of these newspaper accounts points to the general knowledge that the Hangman’s Grove was a thicket of trees in the area that is southwest of downtown Houston.

An article in the Galveston Daily News of August 5, 1893, offers even more information regarding Hangman’s Grove. The story reported that there were two other hangings that took place at the City’s Hangman’s Grove, one, in 1854, was a Mr. Hyde and the other, in 1867, was a Mr. Johnson. After that, hangings took place in the jail yard of the county jail in downtown. These included the executions of Henry Quarles in 1878, John Cone in 1881, Burt Mitchell in 1885, William Caldwell in 1889 and Henry McGee in 1891.

Well into the late 19th century, the cluster of trees that was called Hangman’s Grove was a well- known locale to the people of Houston. Most likely, this was because the grove was still there and had changed little since 1838. It was a landmark on the prairie southwest of town. The clincher in terms of the exact location of Hangman’s Grove, however, comes in 1887. The Galveston Daily News of August 23, 1887, reported that Peter Gabel owned the twenty acre grove of trees in south part of the 4th Ward that was known as old Hangman's Grove. Gabel fenced off the tract and thus blocked several unsurveyed streets including Calhoun Street, Gray Street and Pierce Street, Baker Street, Hopson Street and Crosby Street, Anson Street, Bagby Street and Brazos Street.

So, then, what about the Old Hanging Oak?

John H. S. Stanley built his homestead in the isolated tract on the west side of town in the 1840’s. Stanley was the local representative of Thomas Affleck, a nurseryman in Brenham. He planted a grove of ornamental trees around Stanley home. The Stanley family lived on the property until the 1880’s when it was sold and later acquired by the County in 1895 for a courthouse and jail. The four story courthouse and jail was built on the Stanley land and the large live oak tree which graced the property was left in place to stand at the front entrance to the building. When this courthouse was demolished in 1926 for the construction of a new, eight story courthouse and jail complex, the live oak again survived and became a landmark in its own right at the front of the courthouse.

When asked if any hangings had taken place from the oak, T. A. Binford, who served as the sheriff of Harris County from 1918 to 1937, said that the criminals were hanged from the rafters of the jail, but beneath the tree, the relatives and mourners gathered and waited. In 1942, the live oak at the courthouse was simply referred to as “an immense spreading oak…” By 1984, noted reporter and newsman Ray Miller called it “the Courthouse Oak, also known as the Hanging Oak…” When the City was upgrading the Civic Center complex in the early 1990’s, the marker placed at the tree called it “The Old Hanging Oak”.

No hangings or executions took place at this fine live oak tree. It was called the Courthouse Oak in the past. Wouldn’t this be a better name for our beloved old tree today?